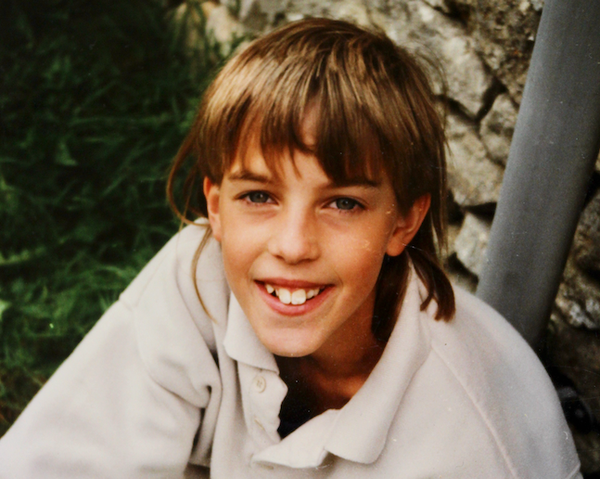

The girl in the photograph is around 10 or 11. She’s wearing beige chinos, a sweatshirt, and purple Converse sneakers. She’s crouching down in the grass by a stone wall, and her hair is some sort of a messy layered mullet. She is healthy and smiling in a relaxed way, with wonky teeth too large for her mouth. Above all, she looks like a boy.

I am the girl in the picture. I don’t know exactly when it was taken, but it’s from around 1991. I posted it on Twitter in response to a tweet by Bev Jackson, one of the cofounders of LGB Alliance, a UK organization that campaigns for lesbian, gay, and bisexual rights. Jackson wrote, “Let’s all do our best to promote positive images of tomboys.”

I know why Jackson said this. It was totally normal, until quite recently, for girls to be boyish without interference. Some grew up to be gay or bisexual; many didn’t. Quite a few girls dressed boyishly and had interests typically associated with boys—machines, adventure, Dungeons & Dragons, football—but no one had a problem with it. No one would have dreamed of suggesting that such behavior indicated that the tomboy was really a boy trapped in a girl’s body. In fact, no one said anything about it at all.

Though I am now middle-aged, this wasn’t a very long time ago. Of course, it is always tempting to imagine that one’s childhood coincided with the perfecting of history. But honestly, it is hard to imagine a more emancipated moment. As children and teenagers, we experienced what can only be described as a kind of positive indifference, and at the end of history, no less. We were free to wear what we liked, play whatever games we wanted, and hang out with children of the opposite sex—as long as we were home for dinner.

Between then and now, however, something sinister has occurred: an elevation of the importance of gender over character, identity over becoming. Today, the boyish girl is in danger of being told she was “born in the wrong body,” and whisked off to a gender clinic to begin the journey from puberty blockers to breast removal to reproductive surgery and, ultimately, infertility. Setting children on this path—one that many regret—is an obvious, grotesque harm. We have taken a terribly wrong turn in allowing pharmaceutical companies to construct lifelong patients out of healthy children.

Back then, we were instead encouraged to develop our interests and character in whatever direction we chose, regardless of sex. Grunge was great, its downbeat heart aside, as we could all just wear a band T-shirt, a checked flannel, jeans, and boots. When Kurt Cobain wore a dress, he did so not because he imagined himself “really” a woman, as some claim today, but because he knew how arbitrary gendered clothing was. There was no denying reality—everybody had a particular kind of body and that brought with it certain truths. As early teens at secondary school, we were separated into boys and girls one afternoon for a brisk overview of the facts of adolescence. It was more amusing than traumatic, and most of us knew it all (at least in theory) already.

“We never imagined that we could opt out of our bodies.”

We never imagined that we could opt out of our bodies. The idea that one could “change sex” or pause puberty would have seemed incomprehensible then. Besides, we wanted to grow up. And even then we knew that this entailed confronting suffering. To be an adult means accepting loss, pain, and responsibility. Our culture has become increasingly unable to do this. We now live in an infantile, padded world where everyone is treated as fragile and in need of protection from potential upset. But this cosseting is more harmful than what it seeks to prevent. It places experience itself on hold, the very process that allows everyone to understand that life is frequently unfair and upsetting, but also shows them how to deal with it.

Children must be allowed to grow up without having their normal behavior pathologized. Adults must face up to their duty to protect children and teenagers from their own desires and not to imagine that their children know best. There was a time when without interference, though not without guidance, we were permitted to become adults, with passions of all kinds. We must recover that time.

I grew out of being a tomboy and became more feminine in my early 20s, but if you’d have asked me at 11 if I wanted to be a boy, I would have said, “Yes.” What would have been a youthful whim, based on nothing more than identifying with my friends, would today perhaps be seen as my staking out some deeper truth about this mysterious contemporary idol named “gender.” But idols are merely gaudy distractions. The subject of the photograph may seem boyish, but that person was a girl then, and is a woman now, and this reality is beautiful to me.