Last week, The New York Times published an editorial bemoaning the fact that Americans feel constrained in expressing their opinions. In a survey conducted by Siena College, 46 percent of respondents reported feeling less free to talk about politics than they did a decade ago. This Very Serious, data-driven, marquee article comes almost two decades after the emergence of “call-out culture”—an intra-left phenomenon in which organizers and activists granted themselves permission to publicly savage one another over race, gender, sexual relations, and all other third-rail political topics. By the 2010s, the social contagion had escaped the confines of the left-activist lab and mutated into the “cancel culture” that many of us either live in fear of, or deny exists.

But, as the story goes, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Right-wingers are currently in hysterics trying to push back against what they see as publicly sanctioned discrimination against white Americans. Chris Rufo, a conservative activist, has skillfully agitated for suppressing race essentialism in classroom settings. His campaign against critical race theory has been met with much enthusiasm on the right.

Frankly, I am less interested in the merits of one or the other position—Does Drag Queen Story Hour at local libraries go too far? Should biblical scripture be studied as divinely inspired in public schools?—than I am in the purpose such Very Serious Consternation over the issue serves. The truth is that whichever wing of liberal capital is in political ascendancy—be it the conservatives or the progressives—its preferred censorship regime will spread through civil society, institutions, and individuals until it is so deeply internalized that most people reflexively conform to it.

One of the earliest thinkers to come close to recognizing this phenomenon was Alexis de Tocqueville, whose nine-month tour of the United States in 1835 birthed one of the finest examinations of American society to date. In Democracy in America, he explained that, unlike the feudal monarchies of old, the circumscription of speech in America came not at the barrel of a gun, but through democratic dissemination:

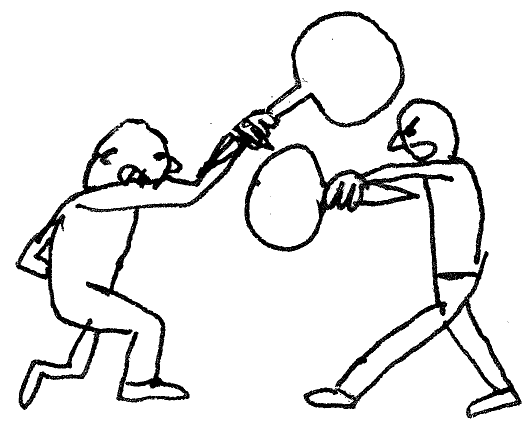

Under the absolute government of one alone, despotism struck the body crudely, so as to reach the soul; and the soul, escaping from those blows, rose gloriously above it; but in democratic republics, tyranny does not proceed in this way; it leaves the body and goes straight for the soul. The master no longer says to it: You shall think as I do or you shall die; he says: You are free not to think as I do; your life, your goods, everything remains to you; but from this day on, you are a stranger among us. . . . You shall remain among men, but you shall lose your rights of humanity.

Tocqueville’s observation is astute, but his error was in excusing those prevailing speech codes as the ironic but natural result of liberal-democratic rule, rather than the oblique application of ruling-class ideology. That is to say, there is nothing illiberal about censorship; it is through the constraint of speech that our ruling class and its bourgeois enforcement arm maintain the fiction of democratic legitimacy. The back-and-forth debate over it only exists to reinforce the public myth of liberalism’s free-speech ideal.

“There is nothing illiberal about censorship.”

Consider the fact that some of the same conservatives who spent the last third of the 20th century promoting protestant Christian “family values” through the banning of gays in the armed forces now leverage that same demographic as justification for “humanitarian” military intervention abroad. Consider also the activist left’s resistance to the Reagan White House’s unofficial gag order on public discussion of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, and then, barely a decade later, when the Democratic Party held the executive branch, the push for what was at the time called “political correctness”—a speech rubric spearheaded by many of the same left organizers.

In other words, today conservatives are out of power and railing against the canceling of comedians who make jokes about transgender people; tomorrow, the same people may be in power and leading the charge in favor of a ban against transgenderism in schools. This is borne out by the Times editorial. Per the survey, 66 percent of respondents agreed that democracy is built on the free and open exchange of ideas, yet a whole 30 percent also allowed for the curbing of speech if it runs afoul of acceptable etiquette.

The contours of the free-speech debate may change, but the fundamental characteristics remain the same—from the Founding to the present day. Self-determination and the ideal of unrestrained speech are essential mythological inventions of liberalism, even if liberalism is constitutionally incapable of following through on its promises. We must ensure that whatever comes next—be it socialism, or some new federative arrangement that hasn’t even been imagined yet—that the promises of such ideals are retained and actually fulfilled.