Social construction is a powerful social-scientific concept with a contentious popular reputation. Most people misunderstand the concept, including those who like to use it. And while it isn’t surprising that social construction has become a shibboleth in our hyper-politicized age, the irony is that people who invoke the concept sometimes take umbrage at its applications, while the people who denounce it end up relying on it as well.

“What I personally believe matters less than what we collectively believe.”

Philip K. Dick, the science-fiction writer, described reality as “that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” But he also asked, “If reality differs from person to person, can we speak of reality singular, or shouldn’t we really be talking about plural realities?” This is where social construction of reality differs from merely idiosyncratic perception. In their definitive work on the subject, The Social Construction of Reality, the sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann emphasize “intersubjectivity” or shared perceptions as a means by which reality is constructed. Thus a corollary to Dick’s definition of reality is that a social consensus doesn’t go away when you personally stop believing in it.

Material reality matters, but so does social consensus. If I do not believe in gravity, I will still plummet to my death upon walking off a cliff. A similar fate may await me if I, as a non-believer in Islam, conspicuously blaspheme against Allah and his prophet on a visit to Pakistan. If I, alone among all the members of my paleolithic Amazonian tribe, understand modern genetics, it is still in my interests to encourage my friends who share the tribe’s consensus belief in partible paternity to sleep with my pregnant wife and thereby neither seem like a mate-guarding weirdo nor deny my future child the social support of several co-fathers. That is, what I personally believe matters less than what we collectively believe. There is an interesting tension when our collective beliefs only partially mesh with material reality.

Here is a simple rule: Most claims of the form “X is socially constructed” are true, but most claims of the form “X is just a social construct” are false. That is, while most of our cultural understandings include more or less arbitrary shared understandings, material reality also constrains our shared understandings. You can find cultures that associate magical power with males and those that associate magical power with females, but no culture anywhere believes that the average female is taller and physically stronger than the average male. Several fields that thoroughly embrace social constructionism—archaeology, cultural anthropology, and science and technology studies—see no contradiction in recognizing the concept of “materiality” which acknowledges that the empirical physical properties of objects provide real constraints on how people interact with them. Physical reality doesn’t strictly determine human culture, but you will scour the ethnographic record in vain for a culture that makes axe blades out of grass. How cultures understand phenomena is tied, but only imperfectly, to objective physical reality. Plato was right that nature has joints at which we can cut it, but a visit to a Chinese poultry butcher suggests we can cut meat in places other than its joints. The same goes for culture.

Consider race, which we are often told (correctly) is socially constructed and (incorrectly) is just a social construct. Race is real insofar as we are not surprised when babies resemble their parents. We also know some genetic disorders are most common in certain ancestry groups, and can crudely estimate where someone’s ancestors lived 500 years ago by glancing at them, and with tremendous accuracy and precision by asking them to spit in a tube and mail it to 23&Me. Race is socially constructed insofar as 23&Me (accurately) reports my results as half “Northwestern European” and half “Ashkenazi Jewish” rather than (with equal accuracy) as a blend of Early European Farmer, Western Hunter-Gatherer, Natufian, and Yamnaya or (with even more accuracy but less precision) that all of my ancestry is part of the Out of Africa clade with some Neanderthal admixture.

Likewise, race is socially constructed insofar as the US Census expects people like me to check the box “white” whereas our Pakistani-American and Korean-American neighbors are both instructed to check the box “Asian,” even though Pakistanis are genetically and linguistically closer to Europeans than they are to Koreans. It is true that the geneticist and the linguist would lump Europeans and Pakistanis, while the US government lumps Pakistanis and Koreans. But that does not mean that “Indo-European” is a real category and “Asian” is a fake category. Even if we assume the linguist and geneticist know their business, it is subjective whether we should base our racial taxonomy on linguistics and genetics rather than historical notions such as Christendom versus the Orient, the “common sense” of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), or the fact that Asian pan-ethnicity has come to feel natural to many people in the roughly 50 years since it was constructed by the federal government.

Notably, social construction encompasses even those who are dissatisfied with a social understanding, so long as they comprehend it. Consider the gender-critical slogan “there are only two genders.” This statement confuses an empirical claim about gender with an empirical claim about the number of sexes, or with a normative statement such as “gender ought to go back to reflecting that there are only two sexes.” Taken literally, the statement “there are only two genders” is a factually incorrect statement about the United States in the early 2020s. Anyone reading this not only knows what “nonbinary” means in the context of gender but can also provide a list of reasonably accurate stereotypes about what nonbinary people tend to be like—born after 1990, multi-hued dyed hair, female, politically to the far left.

“People who describe gender as a social construction often deny that gender identities can spread socially.”

If someone with pink hair walks up to you and says, “I’m Alex and I use they/them pronouns,” you might think, “Got it, I will strive to be inclusive and respect their identity,” or you might think “This crazy girl is gonna be trouble.” But you are not going to think, “Huh, what does that mean?” Saying “There are only two genders” is less like saying “There are only two protons in helium” than it is like saying “The National League in baseball should have held out against adopting the designated hitter rule, given the inherent nature of the game.”

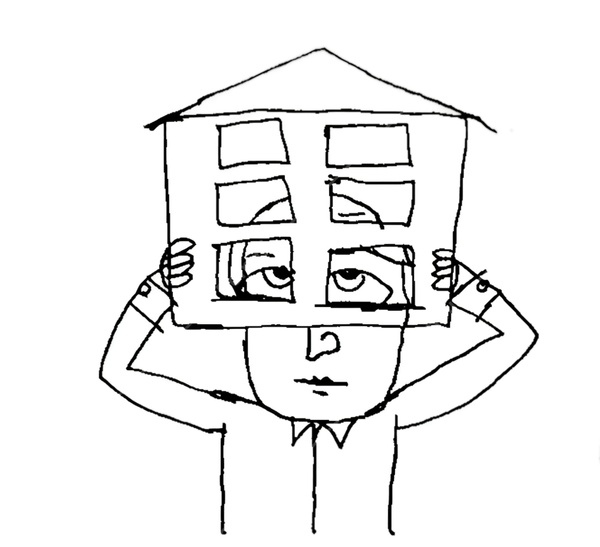

Part of the appeal of declaring something “just a social construct” is the mistaken belief that this gives you power over it. In the 1999 science-fiction film The Matrix, one acquires superhuman powers simply through learning that Chicago is an illusion. Those who are most excited by the idea of social construction impute a false corollary that recognizing social constructs gives you power over them. This fallacy emphasizes the contingency implied by “construction” and ignores the intersubjectivity implied by “social.” I think of this as the ruby slippers version of social constructionism. “Why, Dorothy, you’ve been able to solve inequality the whole time. Just click your heels three times and say, ‘Race is a social construct. Race is a social construct. Race is a social construct.’”

The appeal of identifying a verbal incantation through which one can reshape reality is most appealing to those who are dissatisfied with the world as it is currently constituted. Traditionally, the left has invoked social construction to critique and reform social institutions. The terms “social construct” and “socially constructed” have become so associated with anti-establishment dissent that they have attained shibboleth status as markers of the identitarian left. This has a few ironies attached to it. The minor one is that Peter Berger, who co-authored The Social Construction of Reality, was a political conservative. The more substantive irony is that in some important areas, the right makes social-constructionist claims that the left rejects in favor of a naive epistemology.

Consider the creed of disabilities-studies scholars that disability is socially constructed. By this they generally mean that while impairments are material reality, it is socially contingent which impairments inhibit life or are the basis of stigma. For instance, I have mildly arthritic knees and so I can’t run or take the stairs more than a few times a day without pain. This impairment might preclude a job as a delivery man, but I hardly notice this impairment most days because I have a laptop job and am thus not “disabled.” Nor do I worry anyone will call me an “arthie,” a slur I just made up because having arthritis in your knees is not actually stigmatized in our society. While disabilities scholars and activists sometimes go overboard with this to the extent of being impairment denialists, the basic distinction between material impairment and socially constructed disability is a sound one.

That said, the easiest way to offend disability activists is not to deny that disabilities are socially constructed, but to take this theory seriously. One can reliably attract the insult “ableist” by noting that identification with disability responds to incentives and mimesis. For instance, young women claiming “Tourette’s syndrome” and modeling its symptoms poorly do not have a genuine neurological disorder but are engaging in a mass sociogenic illness spread via social media. Likewise, age-adjusted rates of people claiming disability have risen throughout the global north, and this trend is especially pronounced in generous welfare states like the Netherlands. Rates of “invisible disabilities,” such as anxiety and ADHD, have risen dramatically in both K-12 and higher education as these diagnoses provide access to resources like extra time on tests. But noticing this is ableist if you follow the heuristic that interpretation of disability as socially constructed is valid only insofar as it supports greater social accommodations.

An even more pronounced example is gender. Imagine two ways of understanding a decade of exponential growth in female teenagers announcing they are not in fact girls but either boys or nonbinary. The first viewpoint is that there is a deep ontological reality to transgender identity such that these young people are only now revealing who they really are because of declining stigma and increased public representation. The second viewpoint is that rapid onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) spreads as a social contagion. Both of these viewpoints treat gender as socially constructed, but the ROGD model does so in a much more thoroughgoing fashion. After all, if anything can be described as “just” a social construction, it is a culture-bound syndrome spread as a mass sociogenic contagion. And yet we face the irony that people who describe gender as a social construction often deny that gender identities can spread socially (as if public models of transgenderism would only affect those for whom it was their “real” identity). Whereas those who believe that gender identities spread socially often describe themselves as “gender critical” or state “gender is not a social construct.” It is as if self-described gourmands subsisted on soylent and self-described ascetics made nightly 12-course meals featuring ortolan.

Social construction is in a curious position of alternately being exaggerated and denied. The reality is that social construction is a powerful tool, but not a magical one. Understanding that something is socially constructed does not render it meaningless, but it does let us understand how we came to have pan-ethnicities like “Asian” and “Latino,” how changes in the measurement of record sales led to an apparent boom in country music, and why law schools give temp jobs to otherwise unemployed recent graduates. Social consensus is constrained by material reality, but not as much as those disgruntled by the excesses of social constructionism assert. And the greatest irony is that the polarization over social construction has grown so strong that some who embrace the term deny its implications, and vice versa.