In the early 1860s, a middle-aged Karl Marx was facing one crisis after another. He lost his lucrative job as the London correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune. His wife, Jenny, almost died of smallpox. Money was scarce, and there were several children to feed. Nobody was reading his decade-plus-old Manifesto, and Das Kapital was still only a pipe dream. To cope, the socialist philosopher turned to that age-old male spiritual practice: thinking about the Roman Empire, every day.

Some have detected in the recent viral meme (“How often do men think about ancient Rome?”) more evidence of a worrying rise in right-wing extremism. For years, classicists have been sounding the alarm about nefarious links between fascism and online male fans of antiquity. But not long ago, some of Rome’s great men fascinated thinkers and activists of the left.

Reading Appian’s Roman Civil Wars in the original Greek, Marx was particularly struck by one figure. He wrote to his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels: “Spartacus emerges as one of the best characters in the whole of ancient history. A great general (unlike Garibaldi), a noble character, a genuine representative of the ancient proletariat.”

Spartacus was the gladiator who shocked the Roman world by leading a slave revolt that almost succeeded in breaking free of Rome’s grasp around 73 B.C. Even before Marx, his example had captivated radicals: The Haitian revolutionary general Toussaint L’Ouverture was hailed as a “Black Spartacus” in the early 19th century—a comparison recalled by another Caribbean revolutionary, Fidel Castro.

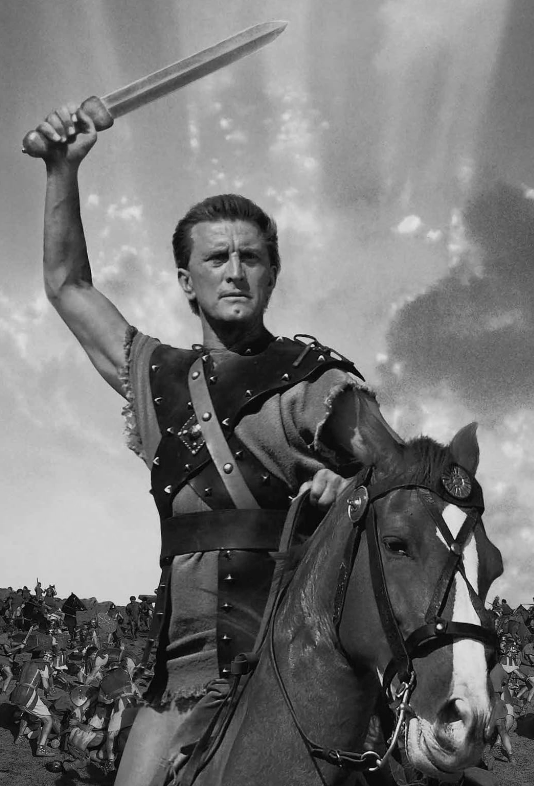

Most people’s familiarity with the figure of Spartacus today comes through the 1960 film about him starring Kirk Douglas and Laurence Olivier and directed by Stanley Kubrick. In terms of its genre and aesthetic, Kubrick’s Spartacus drew on a palette pioneered by reactionaries: namely, the Italian peplum and Maciste films, which chronicled the adventures of a fictional muscleman invented by the proto-fascist author Gabriele D’Annunzio in his screenplay for the 1914 silent film Cabiria, set in the ancient Roman world. Spartacus borrowed many important elements from Cabiria and its successors—above all, a focus on muscular male bodies in action sequences. However, the film’s deeper message emerged from an entirely different ideological matrix.

While he was in jail for refusing to disclose the names of fellow Communists to the House Un-American Activities Committee, the novelist Howard Fast became interested in the life and writings of an earlier Marxist, the murdered Polish-German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, who had adopted Spartacus’s name for the far-left political and paramilitary organization she co-founded in 1914: The Spartakusbund, or Spartacus Brigade, challenged the German Social Democrats for leadership of the country’s left. This effort culminated in a failed coup attempt in which 150 to 200 Spartacus Brigade members were killed, including Luxemburg.

Fast’s 1951 historical novel, Spartacus, on which the 1960 movie was based, was the fruit of his fascination with Luxemburg. The author appreciated Luxemburg’s emphasis on the importance of historical symbols to motivate political action. Despite the overt political commitments of its author, Spartacus was broad enough in its appeal to themes of freedom and solidarity that Hollywood leading man Douglas—a lifelong Democrat, but not a revolutionary—was captivated. Douglas opted to produce the film with his own independent studio and play its starring role. He approached Fast for a screenplay, but the resulting adaptation was appalling, so the blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was brought in to execute the transition to film.

The film was a smash success at the box office and garnered four Academy Awards, but Trumbo was disappointed. The final version of Spartacus failed to do justice, in his view, to his revolutionary hopes. It was communist enough, however, to attract a boycott from the powerful Catholic Legion of Decency, and the revelation that it was scripted by a blacklisted screenwriter provoked further protestations. President John F. Kennedy went to see it anyway.

For his part, Douglas was pleased with the film. He later wrote about the personal inspiration that drove him to make it: “Looking at these ruins, and at the Sphinx and the pyramids in Egypt, at the palaces in India, I wince. I see thousands of slaves carrying rocks, beaten, starved, crushed, dying. I identify with them … That would have been my family, me.” Many others shared his identification with the downtrodden of ancient Rome. Appearing in theaters at the beginning of the 1960s, just as the civil-rights movement was taking off, the film contributed to the emancipatory mood that culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Spartacus, in its current form, would probably not make it past today’s progressive cultural gatekeepers. Frivolous women are the ones to blame for triggering the gladiators’ revolt; Spartacus’s wife is stereotypically feminine and passive; the fight scenes are purely male affairs; and the one black character dies too early. To underscore the Romans’ decadence and corruption, the film (like the novel) portrays its villain, Crassus, as a bisexual predator. Even beyond these “problematic” details, Spartacus isn’t the kind of film that would be likely to appear at a nearby multiplex today. Hollywood seems unable today to offer viewers any real, forceful male heroes drawn from the distant past (Uhtred son of Uhtred of The Last Kingdom is basically fictional). It seems the current pop consensus, shaped by the demands of diversity, equity, and inclusion, would prefer, in the mode of the ancient lawgivers, to consign most of what came before the 1960s—or 2000s—to “the bad times before good order was established.”

If that analysis is anywhere close to the mark, it is ironic that one of the men to whom the presentist status quo is often attributed was deeply affected by Rosa Luxemburg’s Spartacus Brigade. As a young man, the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse carried a rifle in a left-wing paramilitary unit in Berlin and flirted with the idea of joining up with the Spartakusband. But in 1919, after seeing the brigade fail in a bloody disaster, its leaders summarily executed and their bodies dumped in a canal, Marcuse concluded that the hoped-for worldwide revolution had been firmly and finally suppressed in his own land. At that point, he swore off practical politics, entered academia, and went on to develop ideas that would prove hugely influential on the New Left—whose ideological successors went on to shape the current cultural consensus.

Here we arrive at the point in history where the question of how often a man thinks of the ancient Romans can become a funny meme. The meme is funny partly because the women asking the question are so shocked, but also because the Romans are so self-evidently interesting to their men. This disconnect is the result of the consignment of so much of the past to what Leon Trotsky—who himself once went on a tour of the Roman ruins of Italy—called the “dustbin of history.” In this context, the grassroots popularity of Rome among regular dudes should be encouraging for anyone who would like to see a return to a robust historical consciousness.

“It is unlikely anyone will risk death in the name of the Wakanda Brigade.”

As Marx, Luxemburg, Fast, Trumbo, and Douglas all realized, serious political movements need historical symbols. Rome, being so ancient, universal, and broad in its historical influence, is both a powerful symbol in itself and a vast library of symbols—including not only icons of heroic action, but signs foreboding the decline of greatness. Symbols gain more power the longer they live; in other words, the older they are. But they have to be real, too, or credibly real. It is unlikely anyone will risk death in the name of the Wakanda Brigade.

Because of the success of the patriarchy-smashing cultural revolution that has rendered much of history problematic, a public education has not for some time afforded recent generations of Americans much awareness of the potentialities of the past. In the precincts of higher education, meanwhile, classicists are too preoccupied with counteracting the whiteness of the discipline or smashing glass ceilings with female translations of ancient epics to address the problem (if they could even admit it was one). Hence, the only safe space left for men to think about ancient Rome is the internet—to the evident consternation of many women, as well as the media.

The academic and media establishment’s abandonment of the serious task of inspiring men doesn’t bode well for the left’s political prospects. Revolutionary Marxism captured the hopes of earlier generations because it had the fruits of a real culture still in place; Marx himself had his German gymnasium education to thank for his classical learning. The contemporary left’s willful abandonment of much of the historical past leaves it unable to execute the total rupture of history its architects promised. Perhaps, in this sense, progressives have good reason to be concerned that they have ceded the Roman Empire to their legions of online enemies.