The Venerable Bede relates how Pope Gregory I, upon encountering two boys in a slave market, is told they are Angles. This word itself then tells him that they and their people are destined to be “coheirs” of the angels, and through Bede’s ears—or imagination—the prophetic slippage enters history. In this moment, English vindicates itself definitively. Solemn Providence is initially exemplified.

“It is common Scripture that makes a people.”

It is common Scripture that makes a people. By English Scripture, here, is meant our canon–an essentially controversial conception, in multiple respects. The cultural and institutional space it occupies is roughly that of a national church, of which none exists. Its authority is absolute but sublime—“invisible.”

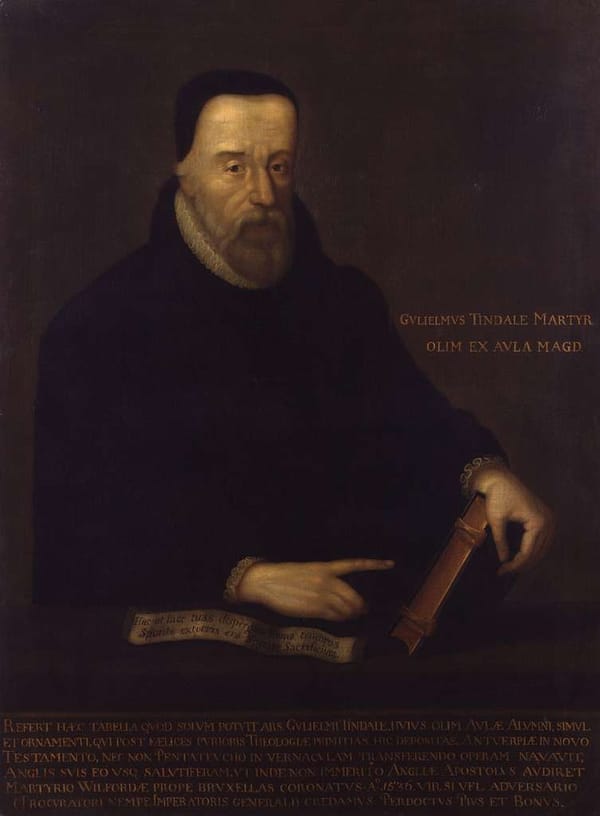

Central to this canon is the Tyndale Bible, superseded by the Authorized King James Version of 1611, and then—forever—by no other. The works of William Shakespeare are equally sacred to it, while the epic poetry of John Milton is scarcely less doctrinally imposing. Its most formidable outposts include the great classics of Adam Smith and Charles Darwin. Those peoples under the direction of such a canon—as though under a supreme law—are called here the English. If this label is not predominantly aggravating, it has failed.